Emume Iwa Ji na Iri Ji Ohuru – Across Igboland and among the Igbo of Nigeria in the diaspora, the month of August, as it is now, is gladdened with the celebration of New Yam called iwa ji and iri ji ohuru. This is best pictured in the framing of the ceremony by Chinua Achebe’s work as far back as in the 1950s.

As Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958) describes: “The pounded yam dish placed in front of the partakers of the festival was as big as a mountain. People had to eat their way through it all night and it was only during the following day when the pounded yam “mountain” had gone down that people on one side recognized and greeted their family members on the other side of the dish for the first time.”

This brief submission explains the significance of the celebration of new yam festival in Igbo society and among the Igbo wherever they may live outside of Igboland. It answers the question, what is new yam and why is new yam such an important ceremony and identity of the Igbo of Nigeria? Why are Igbo children particularly ritually cleansed before partaking in the eating of new yam? The essay adopts a straightforward approach drawing from experience and participation in new yam festivities at home and in diaspora.

New Yam festival in Igboland of Nigeria or among the Igbo and their friends in Diaspora is always marked with pomp and pageantry. The occasion of Iwa Ji and Iri-ji Ohuru or new-yam eating festival is a cultural feast with its deep significance. The individual agrarian communities or subsistence agricultural population groups, have their days for this august occasion during which a range of festivities mark the eating of new yam. To the Igbo, therefore, the day is symbolic of enjoyment after the cultivation season. Yam culture is momentous with hoe-knife life to manage the planting and tending of tuberous requirements. Yam farmers in Isu Njaba of Igboland know this well.

Drawing from Nri, the ancestral clan of Igboland, Dr. Okechukwu Ikejiani states that “?WA JI” (to break new yam) is observed as a public function on certain appointed days of the year. It is the feast of new yam; the breaking of the yam; and harvest is followed by thanksgiving. An offering is put forward and the people pray for renewed life as they eat the new yam. An offering is made to the spirits of the field with special reference to the presiding deity of the yam crop. In the olden days, fowls offered as sacrifice must be carried to the farm and slain there, with the blood being sprinkled on the farm. Yam is cut into some sizes and thrown to the gods and earth with prayers for protection and benevolence. When the ceremony is completed, everything is taken home; the yams are laid up before the “Alusi” (deity) together with all the farming implements, while the fowls boiled and prepared with yam for soup (ji awii, ji mmiri oku) are eaten at the subsequent feast. Everyone is allowed to partake in this and those who are not immediately around are kept portions of the commensal meal.

Another significant aspect of the ritual not discussed by writers in this field is the preparation of children to partake in the eating and celebrating of the new yam – called ritual body wash, imacha ahu iri ji mmiri (consequently, ji mmiri, connotes fresh yam, new yam). The belief is that to take in a new thing into the body, it is important to cleanse the body and in this case a new yam deserves a clean body achieved through dedication and purification ritual. As a child, my own grandfather, a ritual expert and healer, never allowed all the children in our village to mark new yam festival without first of all gathering us together and counselling us on the importance of Ahiajoku, yam productivity and its diverse gender sensitivity, social and cultural miracle. He would lay on the ground some fresh grass and some leaves of ogirishi (newbouldia laevis) and other requirements such as omu (young palm tendril). These are employed to create a ritual space and contact with the earth and Ahiajoku to wash and protect the body. One at a time, each child is made to stand in front of this ritual ground and the ritual expert would render a powerful incantation or prayer while passing around the head and throat a bunch of the materials asking the child to spit out saliva on the ground. Across the body the expert also softly brushes materials as he prays for the good health of the chap to be fit to eat the new yam and celebrate the occasion peacefully. Parents took it upon themselves to present their children to the therapist to undergo the cleaning of the body and enacting accord of order and health in the enduring Igbo new yam festival setting.

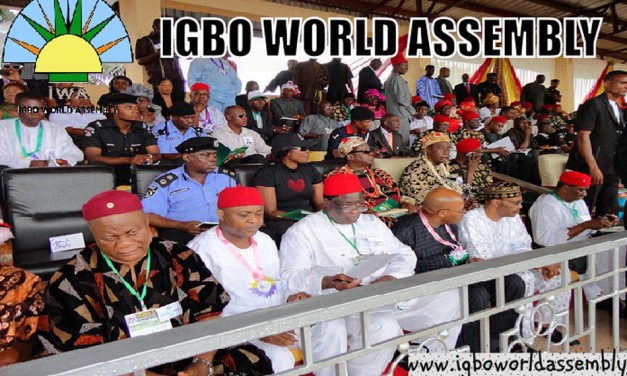

Today, Igbo people in urban centres and in foreign lands celebrate new yam with equal amount of curiosity and zeal to re-engage their life-world and cosmological values. Not long ago, the six geo-political states of the Igbo gathered at the National Theatre in Lagos and uniquely celebrated the New Yam Festival, with Chief Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu and others leading the rite as a unique heritage and integral thing of the Igbo World.

In celebrating the New Yam Festival, the whole community shares in this harvest and thanksgiving called “Afia-ji Oku”. Celebration is extended to the open market squares and streets where spectacular dances, songs and running around in organized groups, including all forms of jubilation and role reversals are played out and hailed in a carnival mood (ima ijere, ima ahia).

As the biggest of yam communal rites, it is described as iri ji ohuru, iri ji mmiri, iro ofo, ofala and ibu ji aro (the latter being common among the people of Ehime in Mbano of Imo State. The Ibu ji aro is the largest market outing fanfare where a unique yam called “ji aro” is jubilantly carried to the big market when it is in full session on a chosen traditional big market day and time by the very head leader of Ahiajoku deity of Umuezeala community in Ehime area. As observed, a special site of Ahiajoku deity around the market is paid homage with prayers and items such as kola nuts, fowls and yams. A thunderously high ovation is echoed by market men and women upon sitting the big yam – ji aro, decorated with young palm tendril, fowl and traditional dancers on approach to the market and inside the market as the celebration catches a moment of pushing and jumping up and down by onlookers to catch a glimpse of the huge yam and the carnivals around it. In Ehime area, new yam cannot be eaten until ji aro goes to and returns from the market of Nkwo Umuezeala. Not only stories held that catastrophes and strange things happen in the locality at any time the rule and taboos around ji aro tradition are violated or ignored but also specific cases and references to individuals and families affected due to subversion against ji aro are commonly and typically known. As such, the community as a whole celebrate and preserve the heritage annually in August called onwa ano Umuezeala (forth month of Umuezeala people). At a time I conducted fieldwork on Igbo Medicine and culture; I had paid attention to the rites of new yam and interacted with the village where ji aro has a high esteem for individual and community renewal. Indeed, the meaning of ji aro can only be fully understood by living with the community and experiencing it firsthand in the month of August every year.

Guests of the celebrating community pour out in large numbers to appreciate their hosts with excitement and applause as dances and songs, shooting of guns by young and old, drumming and sounding of the big wooden gong, and indeed, all else provide a vibrant social ambience of lineage, kinship, neighbourhood, workplace, school, business and friendship connections. Compounds, pathways, local rivers and streams, including markets and deity sites are cleared and kept clean for indigenes and guests to have a feel of the geographical beauty of the community. A community facing new yam festival – from home to stream and market arenas experiences the best of its cleanliness and physical features as an important part of the meaning of the festival also. Different communities describe this aspect as clearing roads festival while others attribute it to mean the same thing as new yam festival which equally connotes harvesting, clearing and cleansing.

Dr. Okechukwu Ikejiani further states that the meaning and significance of the name “Afia-ji Oku” is worth explaining. For him, the idea behind “Afia-ji Oku” seems to indicate exertion, industry, to strive after, hence to trade; “ji”, to lay hold of and “Oku” riches. Thus, the full meaning is: “Industry or trade brings wealth.” In those days, yam largely constituted wealth. A man is evaluated by the size of his yam barn (Oba Ji), large household and ability to earn a good living and help others in society. The rite of new yam is to re-enact a bounty harvest and wealth for the celebrants. The importance is further captured in seeing the new yam festival as a tradition, and one of which culminates the end of a yam farming cycle and the beginning of another. That is perhaps why in Igbo cultural setting, invitation to the festival is open to all and sundry – friends, neighbours, kin relations, acquaintances, in-laws, etc. The carnival mood and graciousness at extending invitations and welcoming every visitor and guest means that there is plenty of food to enjoy as opposed to lack of food to live on.

In Igbo society, the culture of cutting, iwa; and eating, iri; of the first yam is performed by the oldest man in the community or the Eze, King. Privileged by the elder-ship and title-ship positions in society, it is believed the senior members of the community mediate between the ancestors and gods of the land. The totality of rituals around the new yam eating express the community’s appreciation and renewal with the gods for making the harvest of farm yields possible and successful. As confirmed by Dr. Okechukwu Ikejiani and other observers and informants, new yam is not eaten until due rite is accorded to the god of yam called Ahiajoku, ifejioku and ajoku. Igbo people answer names rooted to the deity of yam such as Njoku, Nwanjoku. Also titles are taken after the deity for distinguished farmers such as Eze-Ji, Owa-ji and Mma-ji. In 1979, when Prof. Michael Echeruo delivered the inaugural Ahiajoku Lecture, he carefully observed the deep significance of yam and yam festival as though a male crop, it identifies with a beautiful Igbo cultural identity and heritage. Varieties of the yam tuber were introduced to Igboland in the late 19th century by the Portuguese traders and explorers of farm produce. Along the West African coastal belt, yam cultivation and celebration is also well known. But why new yam festival is highly pronounced in Igbo even more than in other none Igbo yam producing communities is best explained to mean how the Igbo cherish, adore and intensively farm the crop as a key staple commodity with a masculine fanfare. Of course, there are several sexual nuances associated with Ji, yam, king of crops, as a male crop and a male thing. For insight, see Iroegbu Patrick’s book, Marrying Wealth, Marrying Poverty (2007). Marriage in Igboland cannot occur without Ji as a male power, to behold. Cocoa yam is a supportive crop-kin of yam much as male is to female.

Celebrating the New yam fest is common with energetic men’s, women’s and children’s cultural dance troupes, in addition to fashion display, role reversals, Igbo masquerade jamboree, heavy drinking of palm wine, folklores, commensality and reciprocity all of which are synonymous with the iwa ji and iri-ji ohuru in Igbo life and culture.

The Iwa Ji Afo (annual yam cutting) is one of the biggest festivals celebrated by the Igbo beginning in the month of August of each year. Celebration lasts up to December of the year. In the period in which many communities celebrate their new yam festival, marriages are withheld as well as funerals. Serving food during the new yam festival is lavished on dishes of yam since the festival is symbolic of the abundance of the produce. Enough yam is cooked such that no matter how heavily guests and family members may eat, there is always enough at the end of the day. It is, in that sense, a season of merriment, commensality, abundance and hanging out together. Accordingly to Ugo Daniels (2007), this is also noticed in other West African regions such as in some Ghanaian communities where the feast is dubbed “Homowo” or “To Hoot at Hunger” Festival. Here the people ritually mock against famine and apparently hope for a good harvest so no famine will hit the people in the coming year.

Essentially, the harvest of yam and the celebration of the deity of the land given the New Yam festival consist in expression of the people’s religious belief in the supreme deity as a giver of yam and donor of good harvest. With the coming of the new moon in August (onwa ano or onwa asato), marked is the preparation for the grand iri ji ohuru festival; but again the time and mood of preparation varies from one autonomous community to another. The New Yam festival is such a highly appealing event to the extent that dominant religions such as Christianity, in particular, Catholic Dioceses and Parishes have enculturated iwa ji and iri ji ohuru in Christian worship and celebration (cf. Chris Manus 2007). Informants referred to cases where Iri Ji Festival is called Ji Maria, Ji Madonna and Ji Joseph to venerate the Holy Virgin Mary as the Mother Earth and of whole produce to glorify God. This is a development that shows how dynamic cultures are embraced for change and continuity. Typically, New Yam Festival provides a heritage of dances, feasting, renewal of kinship alliances, as well as marks the end of one agricultural season with a harvest to express gratitude and thanksgiving to the society, gods, friends and relations. Thanks to IPUNA, it is a fabulous New Yam Festival in Edmonton of Alberta for the Igbo and their friends. New Yam Fest is as cultural as it brings life, identity renewal, solidarity and progress! Enjoy. Igbo Kwenu!

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

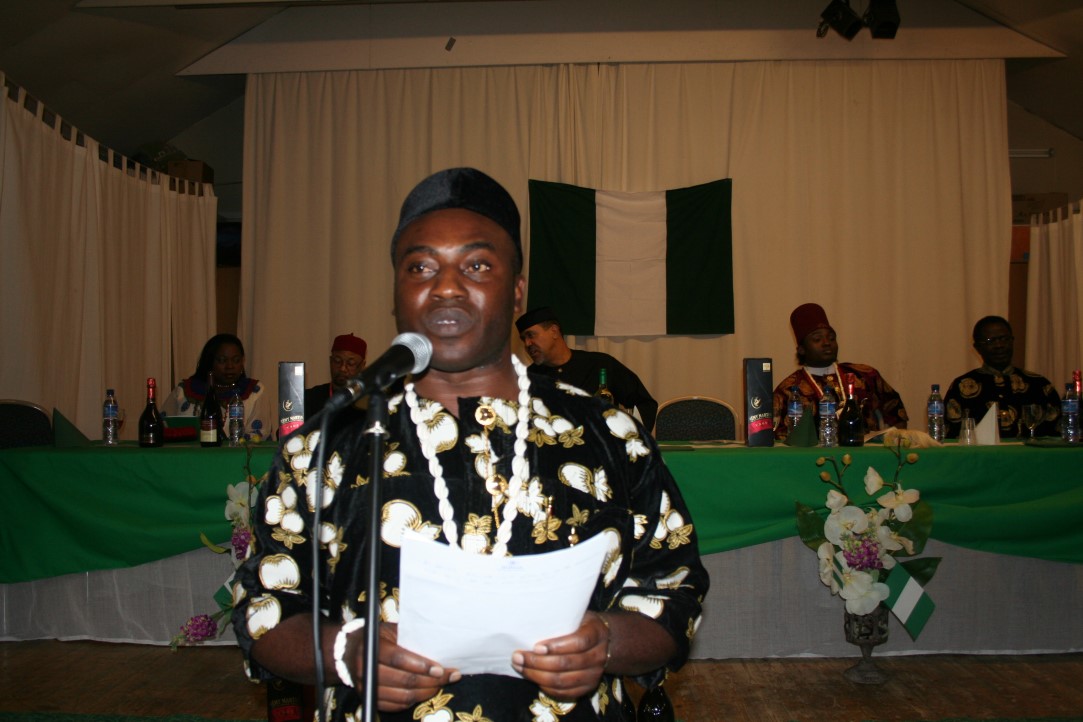

This short essay and speech were presented in the Event Brochure and gathering for the New Yam Festival in Edmonton of Canada (Saturday, July 31, 2010) to mark the Isu Njaba People’s Union of North America in Edmonton – the Host City, for the 2010 Fund Raising Engagement to support school renovations at home (contact: nyfe@edmontonnewyamfestival.com; website: www.edmontonnewyamfestival.com). The Mayor of the City, His Lordship, Stephen Mandel and other High Profile Guests representing the Alberta Premier and various Ministers of Education and Culture witnessed the New Yam Celebration. Dr. Patrick Iroegbu, current President of the Igbo Cultural Association of Edmonton and a published author [see Two New Book Releases: Introduction to Igbo Medicine and Culture in Nigeria (2010) and Healing Insanity: A Study of Igbo Medicine in Contemporary Nigeria (2010) – see website: www.healinginsanityigbomedicine.com/author.htm] mobilized the Igbo in Edmonton for the remarkable event filled with cultural performances and display of rich Igbo cultural heritage. Earlier in the month, Saturday July 3, the association held its stunning 2nd Igbo Cultural Day, 2010 and the news was carried by the Igbo Radio of the Voice of Nigeria also.